What same origin iframes are used for?

04 Dec 2024iframes can either share the origin of their embedder or not. While cross-origin iframes are highly useful and are well-used across the web, what are same-origin iframes used for? Aside for malicious ways to use such iframes, are there any legitimate use cases for them? This research will focus on finding the answer to this question.

In the past months I’ve been focusing on pushing a W3C proposal (within WICG) called Realms-Initialization-Control to address the “same origin concern”. The solution I originally proposed (which may end up being slightly different), attempts to follow the “layering approach”, so that it can be adopted by developers with close to zero fraction. Problem is, the layering approach means introducing a new way to inject JavaScript code into web applications, which might not be ideal. On the other side of that spectrum, more restrictive solutions can be considered, which would be harder to misconfigure and abuse, but might be too restrictive for developers to adopt too.

In this piece I’ll focus on that spectrum and the research I had to make in order to tell which path is more appropriate to choose and why. I thought I’d share my way and findings as they shed light on interesting aspects of the web that weren’t well investigated prior to this.

Unless you’re familiar with my work, about 90% of what I just said won’t make sense to you. Let’s back it up then.

The Same Origin Concern

This is a problem I’ve been vocal about for a few years now. I was first exposed to it by working for PerimeterX on a 3rd party JavaScript runtime security library, which was basically responsible for redefining powerful APIs at runtime within web pages of our customers in order to keep track of their use, mitigate what they can do and more, and by that grant our customers some visibility into potentially bad things that take place on their client side:

window.localStorage.getItem = function(key, secret = '') {

if (secret !== 'AGREED_UPON_SECRET') {

return null // protect access to localStorage items!

}

return localStorage[key]

}

The example above is a reduced one, but it brings the point across - I can redefine the (powerful) localStorage API to behave slightly different, so that in order to access the values it contains, one must provide an agreed upon secret. If that secret is safely shared with trusted parts of the application and not untrusted ones, we could theoretically virtualize this API to be more picky about who can access it and who can’t, which allows us to introduce advanced security controls to already existing capabilities.

That is the essence of what I was working on in PerimeterX (the product was called “Code Defender”), and is referred to as a layering approach because you introduce another layer of logic on top of existing APIs at runtime.

I’m a great advocator of the layering approach, because it amplifies the strengths of the web and JavaScript, being highly dynamic, configurable and expressive technologies - you can redefine pretty much anything to behave pretty much however you want it to, and by that you can invent pretty much any security control to web applications. That is power we should harness.

Problem is, with how the web is designed, there are some major blockers that undermine the layering approach quite significantly.

The one I’m most worried about ever since I realized it working for PerimeterX is the Same Origin Concern, where a web application is granted APIs with which it can create new realms that expose a fresh new set of the same APIs the main realm exposes.

That’s bad news for the layering approach, because it makes it useless - attackers don’t have to obey the mitigated APIs anymore, they can just find fresh instances of them elsewhere:

function getLocalStorageNaively() {

return window.localStorage

}

function getLocalStorageBypass() {

const ifr = document.createElement('iframe')

return document.body.appendChild(ifr).contentWindow.localStorage

}

getLocalStorageNaively().getItem('sensitive_pii') // null

getLocalStorageBypass().getItem('sensitive_pii') // +977-5555-333

I was the first to build and maintain a project that was entirely focused on addressing this problem.

Ironically, it was the layering approach on top of which the snow project relied, and it was quickly acquired by MetaMask’s new security project LavaMoat, making this project the only one building against this issue in public as an open sourced software.

All snow did was to take your mitigating code (such as the localStorage example) and make sure it runs against every new same origin realm (e.g. iframes/popups), thus eliminating the ability for attackers to leverage the same origin concern to escape the security controls you dictated to your web page:

// Use Snow

SNOW((win) => {

win.localStorage.getItem = function(key, secret = '') {

if (secret !== 'AGREED_UPON_SECRET') {

return null // protect access to localStorage items!

}

return localStorage[key]

}

})

// Snow protects same origin realms

getLocalStorageNaively().getItem('sensitive_pii') // null

getLocalStorageBypass().getItem('sensitive_pii') // null

A happy ending?

Well, not quite.

Sadly, solving this problem at user-land (by using JavaScript at runtime), is basically impossible due to some core characteristics of the web’s design. You can learn more about that by browsing through the many open issues that were left against the snow repository. Some are addressable, some aren’t.

This made things clear - addressing the same origin concern must become a browser native solution.

The Realms-Initialization-Control proposal

The idea was to migrate the exact value snow brings into the browser, and a proposal was submitted against the Web Incubator Community Group.

Both Shopify and Akamai showed enough interest in such a solution which helped officially getting it in to the incubating program, and with Yoav Weiss’s help, I’ve been working on it ever since.

So the idea is very similar to snow’s approach - provide developers some API to declare some path to a remote script with, and make the browser load that script for every new same origin realm that comes to existence.

Based on the previous example, by placing the same localStorage security controls in a remote script /scripts/realm.js:

window.localStorage.getItem = function(key, secret = '') {

if (secret !== 'AGREED_UPON_SECRET') {

return null // protect access to localStorage items!

}

return localStorage[key]

}

And delivering it via the new proposed API (for example, via the CSP header):

CSP: "run-on-same-origin-realm /scripts/realm.js"

Would theoretically provide the same value snow does:

<html>

<script>

localStorage.getItem('sensitive_pii') // null

</script>

<iframe id="xyz" src="about:blank"></iframe>

<script>

const ifr = document.getElementById('xyz');

ifr.contentWindow.getItem('sensitive_pii') // null

</script>

</html>

Only this would be more resilient and secure given it is implemented by the browser.

Sounds like a plan, right?

The spectrum

Google’s Artur and David, who participate in W3C as well and care about such proposals, brought up a good point - shipping the proposal at its current state will introduce yet another way to inject JavaScript code into web applications, which would result into more browser internals complexity and potential risk if configured improperly.

Instead, they suggest an alternative proposal they call no-sync, which would basically be a boolean header (false by default) that when is enabled for a certain realm, makes sync access to/from that realm from/to other realms impossible - even if they share the same origin.

On the one end of the spectrum, this no-sync is very strict, because if websites want to make legitimate use of same-origin sync-access features, they won’t be able to do so and adopt it at the same time. But on the other hand, it will eliminate the same origin concern successfully, and will do so without introducing new ways to run JavaScript in new realms and web pages, which might have ended up introducing more complexity to the web.

On the other end of the spectrum, the RIC proposal is way more lax, because it allows achieving both states - more security (by implementing security controls using JavaScript and the layering approach without having to worry about the same origin concern) but without having to disable same-origin sync-access features.

All parties agreed that the answer to this question (“which is the path we should choose?”) will be found if we could tell to which extent does the web depend on the same-origin sync-access feature.

Which is to say, if we learn there aren’t enough websites that make any use of same origin realms such as iframes by synchronously accessing them, then maybe the no-sync idea is something we could go for, but if we learn the opposite, that would mean too many websites rely on this capability, so that shipping the no-sync feature would only serve those who can adapt themselves, which might not be the case for many other websites that will just end up rejecting adoption of such a feature for disabling core functionality they rely on (some claim CSP suffered from a somewhat similar destiny).

Time to find out!

It was decided we run this experiment. The question we ask is:

“do websites form same origin realms and access them synchronously? and if so, how often?”

In order to get there, here are the steps we must take:

- Define what same-origin sync-access is

- Find where this happens within the browser (we’re doing Chromium for close-to arbitrary reasons)

- Introduce some way to keep track of such operations and count them

- Discover the results

Define

What are same-origin sync-access operations?

Basically, it’s the event in which one realm accesses properties of another, given the two realms share the same origin (thus they obey the same origin policy).

Some examples would be:

<script class="top-to-iframe">

window[0];

frames[0];

iframe.contentWindow;

iframe.contentDocument;

</script>

<script class="iframe-to-top">

top;

parent;

</script>

<script class="opener-to-openee">

opened.document;

</script>

<script class="openee-to-opener">

opener.document;

</script>

<iframe srcdoc="<script>parent.document;</script>"></iframe>

<iframe src="javascript:parent.document;"></iframe>

Find

So, where does this happen in the code?

I mean, when realm A tries to access properties of realm B, how does Chromium make sure they belong to the same origin and where exactly does it approve it?

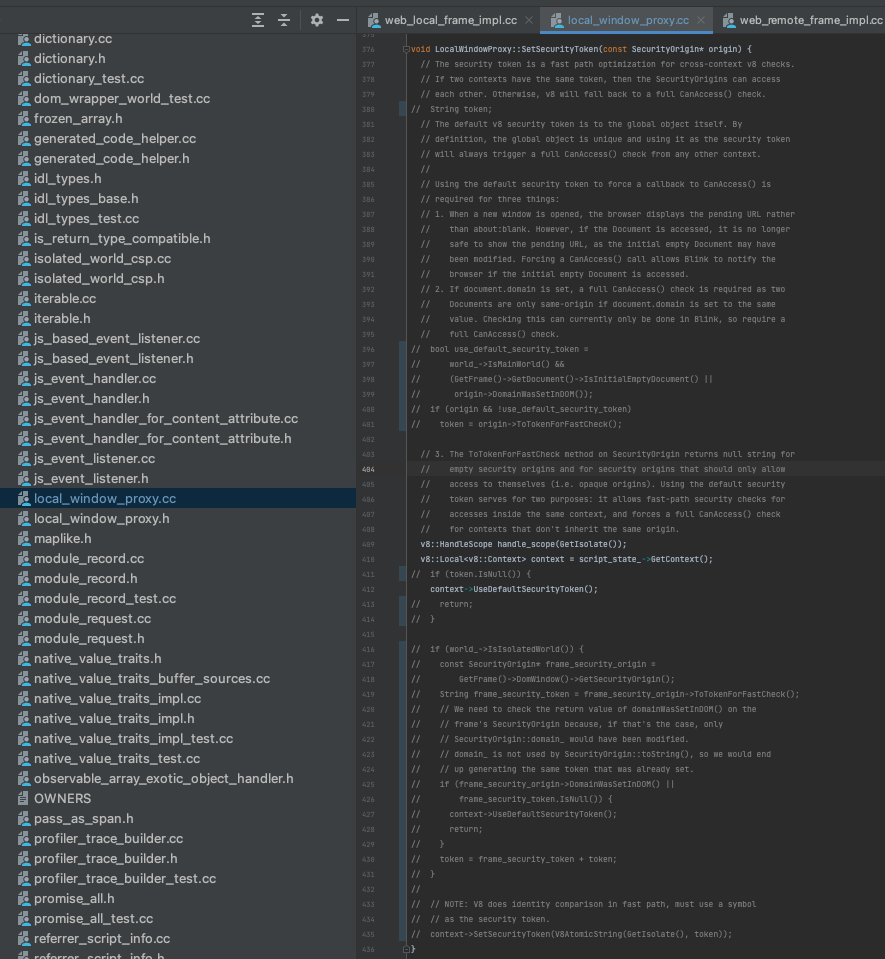

To be honest, it took me a few weeks of research, and I was only somewhat on point, but it turns out there are some interesting things about how origin security takes place within the Chromium source code which would have taken me more time to figure out by myself it wasn’t for the help of Camille and Yuki from Google, which I think are worth sharing.

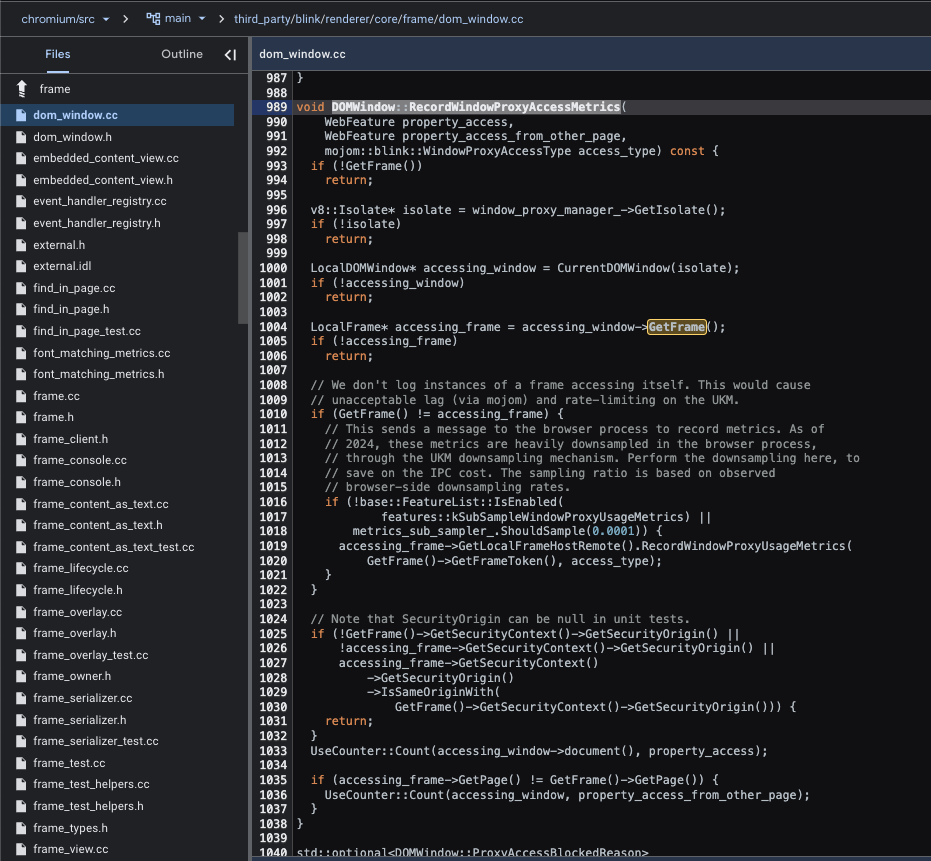

At first, I was looking at DOMWindow::RecordWindowProxyAccessMetrics:

It caught my eye because it was already counting realm-to-realm origin-access related operation, but the exact opposite of what I needed - it counted cross-origin access.

Counters are small chunks of code that tell some remote server when that chunk of code was executed by some remote user (assuming they allowed the browser to share such metrics) so that they can be later aggregated and investigated by browser developers

This particular counter mapped the different properties realms use to access other cross-origin realms, and now they keep track of how often that happens.

So whenever a browser somewhere in the world loads a webpage that loads two realms that are cross-origin to each other, and one of them calls top/parent/etc which resolves to that other realm - that counter counts!

Here’s a list of the properties for which the counter counts:

You can see live results of this counter for yourself - it’s all public (here’s WindowProxyCrossOriginAccessTop for example).

In order to make sure the counter only counts cross-origin access and not same-origin access, it makes sure that’s the case before performing the count. This happens at line 1025 in the attached image above. If the current realm does not share the same origin as the accessing realm - return (as in, bail on counting).

If that’s the case, all we need to do is replace that return statement with some new same-origin counter, right?

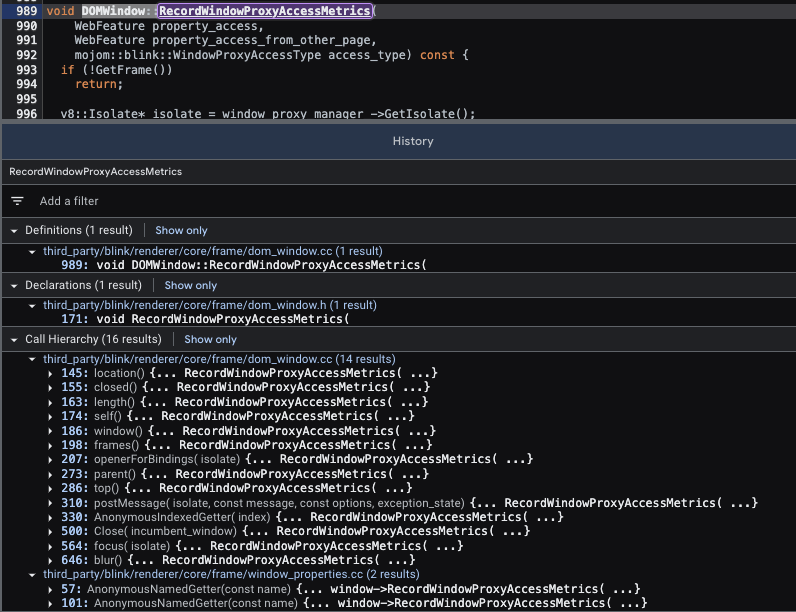

Apparently, it isn’t this simple (the following explanation is based on Google’s Yuki’s explanation to me):

It turns out that when one realm attempts to synchronously access another, the act of checking whether they belong to the same origin or not is very costly in terms of performance, because it means they can potentially be two separate “V8::Contexts” (different rendering processes) if they do not share an origin. This happens within V8’s CrossOriginAccessCheckCallback, which calls SecurityOrigin::CanAccess (where same-origin is determined), and is an act of crossing V8 contexts - which is the performance problematic part.

So, while this is a legitimate method to test for same-origin that would work properly, it won’t scale performance-wise. Therefore, Chromium deploys another technique for avoiding this costly check whenever it can by utilizing what they call a “security token”. The security token is assigned to every new V8::Context (in this case, a realm), and is either a default token, or an origin derived token.

The default token is assigned on some specific cases, to express a refusal to be necessarily friendly to other realms, thus forcing the slow-path check to take place. One example is “opaque origins” which are estranged to other origins by default (e.g. data: or sandboxed iframes). Outside of that, the object representing the security origin of the realm will be set with a non-default token:

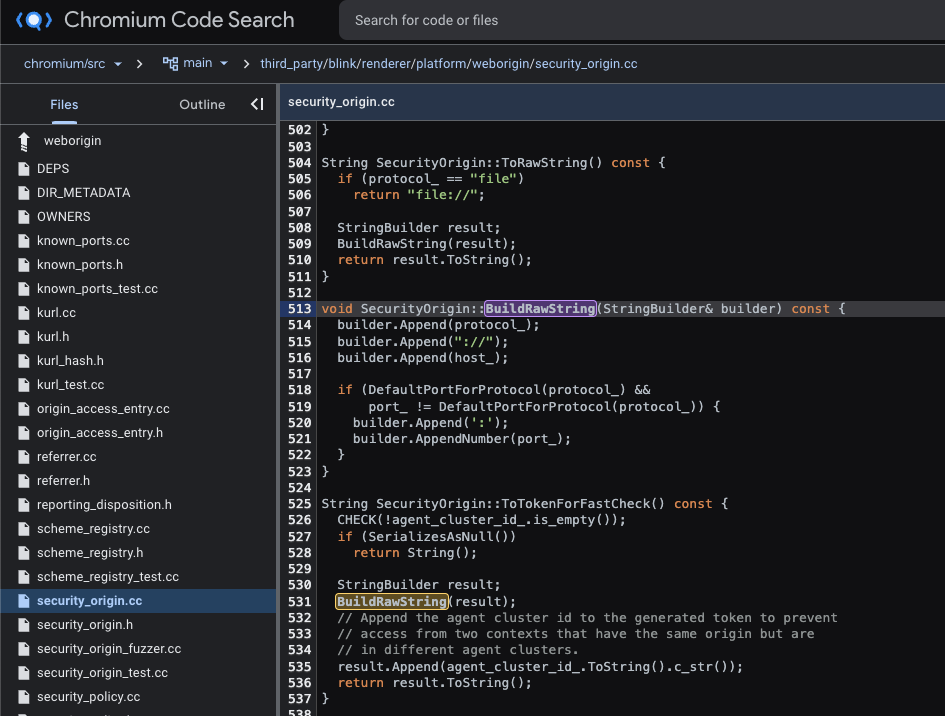

That non-default token will be derived from properties that will necessarily be the same for two same origin realms and different for two cross-origin ones (naturally), which in practice are a combo of the protocol (e.g. http:), the host (e.g. example.com), the port (e.g. 8080) and the id of the hosting agent cluster (because two realms should not have access to each other even if they share on origin if they are hosted by two different agent clusters):

When two realms share an identical token, this security architecture allows telling they both belong to the same origin without having to cross V8 contexts to verify it.

This is pretty cool, and it kind of explains the strange behaviour I observed within RecordWindowProxyAccessMetrics that prevented me from leveraging it for spotting same-origin sync-access operations, where it just would not be called for two different realms that share an origin - the fact they share a security token, making them go through the fast-path, is why they never went through this function (I think).

Introduce

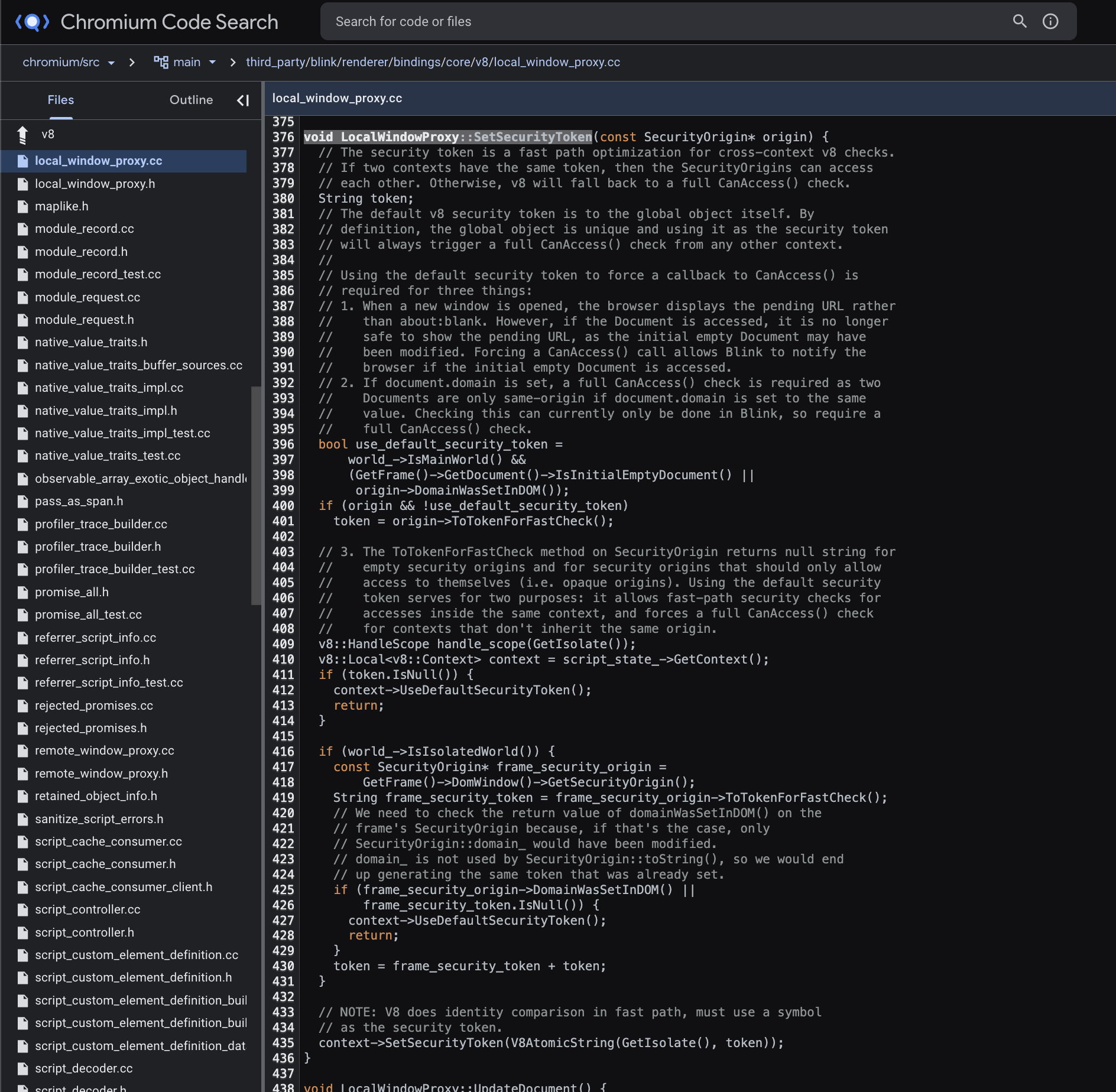

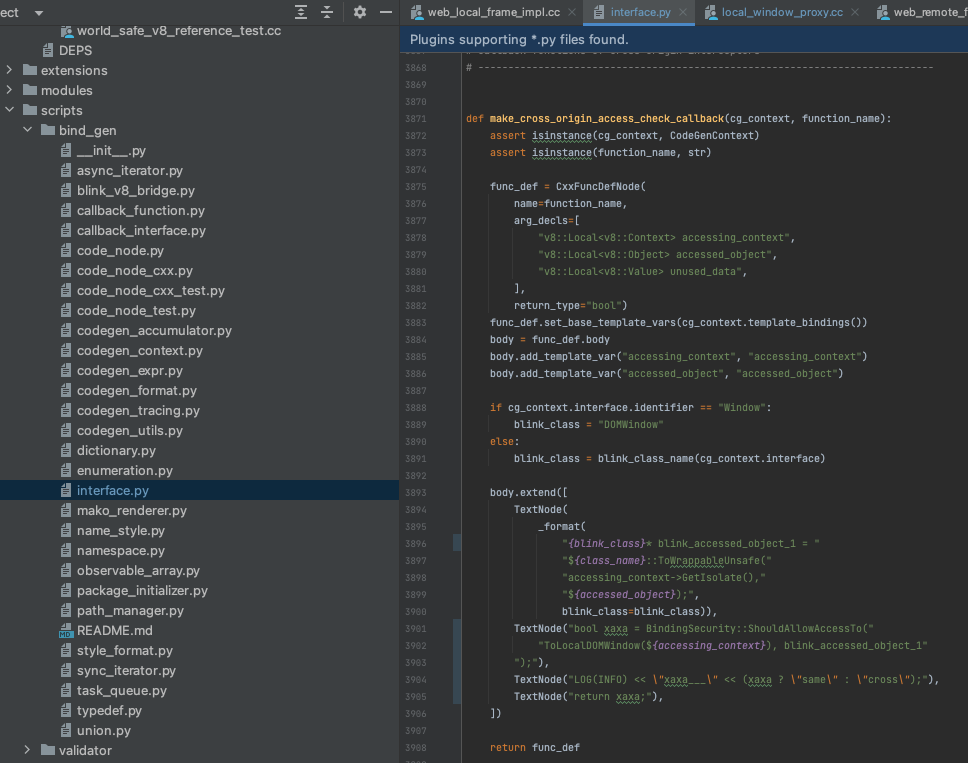

Within this context, Yuki explained how introducing this counter upstream isn’t possible because of the perf issues, and that the right approach would be to apply a change and examine the behaviour locally instead.

The change would be to disable the non-default security token functionality, and force all tokens to be default ones. This would force the slow-path always, but it also means that whenever one realm will try to reach for the internals of another, it will first check whether they share an origin or not through the slow-path, which is where we can successfully inject a counter that can take the origin potential match into account.

So first step is to disable non-default tokens:

Now because of this change, we know that all access attempts (including same origin ones) will be processed by CrossOriginAccessCheckCallback, which asks BindingSecurity::ShouldAllowAccessTo whether access should be allowed (or in other words - do they share an origin?). This means that we should capture the boolean return value into a variable, log it, and pass it on:

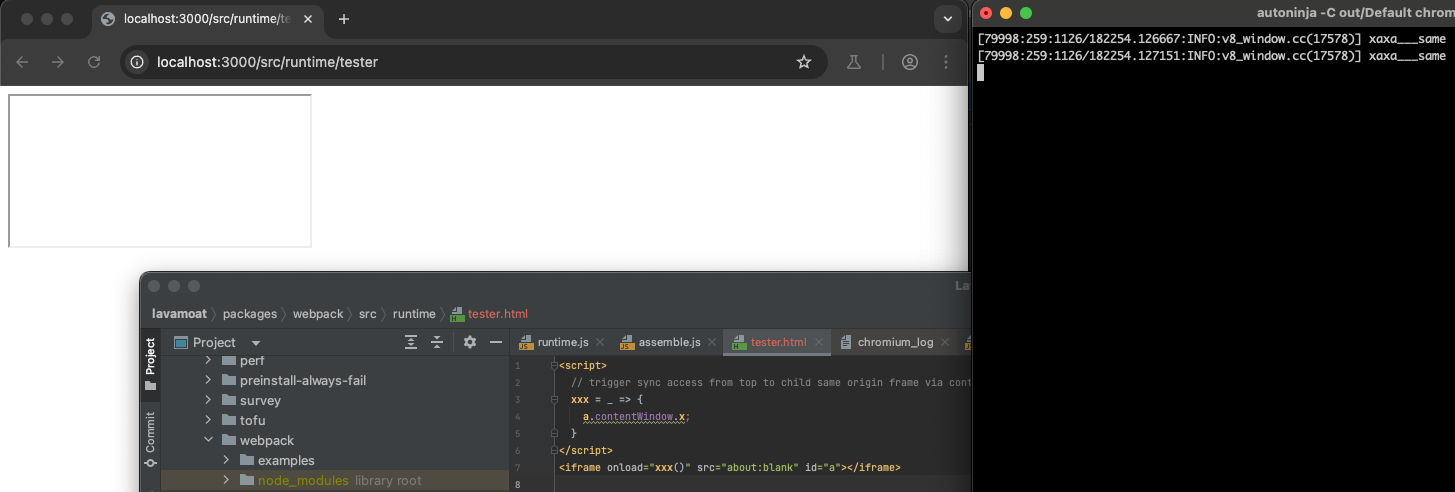

That’s it! Compile, run and it works!

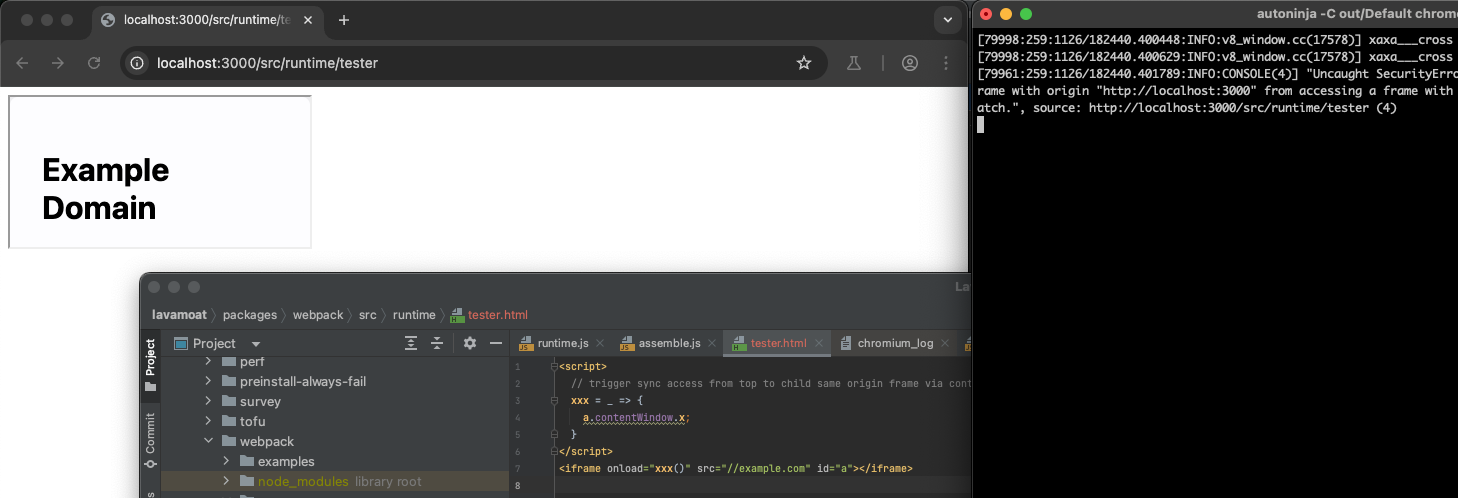

This of course works for cross-origin too:

Discover

Now that we have a local Chromium build that captures and documents realm-to-realm same-origin sync-access occurrences, we can focus on the original goal we had, which is to tell how often such occurrences take place across the web to tell which of the two strategies to protect applications against the same origin concern we should go with. The strategy we’ll go with is to focus on sites that get the highest exposure on the web, which could be one of two entities:

- big websites (most visited ones)

- embeddable sites/scripts (social login pages, popular third party scripts, etc)

Embeddables

Since this could go on forever, we’ll have to stay focused, so for today we’ll stick to the embeddables category, as these have probably more impact given how thousands of websites embed them, so let’s start there.

Google (ads)

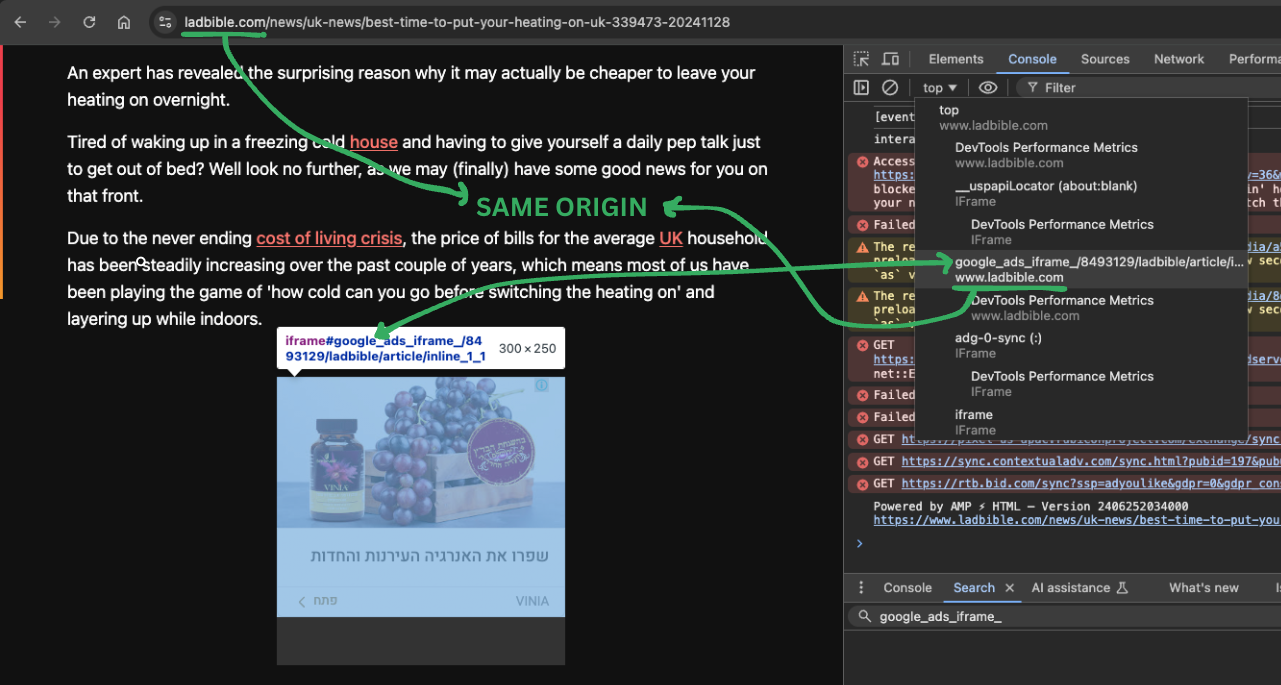

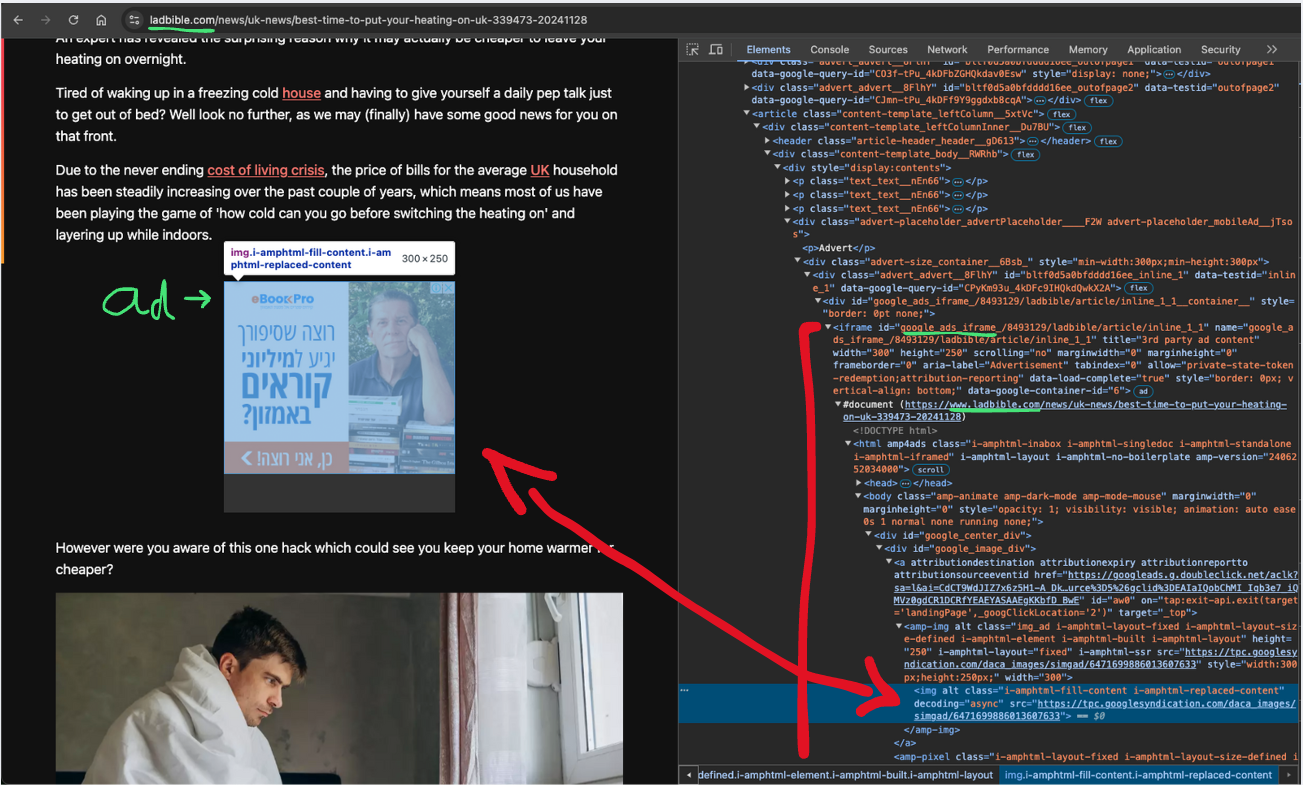

Starting off with https://securepubads.g.doubleclick.net/pagead/managed/js/gpt/m202411180101/pubads_impl.js which seems to be responsible for introducing ads into web pages such as https://www.ladbible.com/news/uk-news/best-time-to-put-your-heating-on-uk-339473-20241128. Quick look shows there are same origin iframes within the page that based on their name and contents are ads that were created by Google’s ad service:

Here’s how its DOM structure looks like:

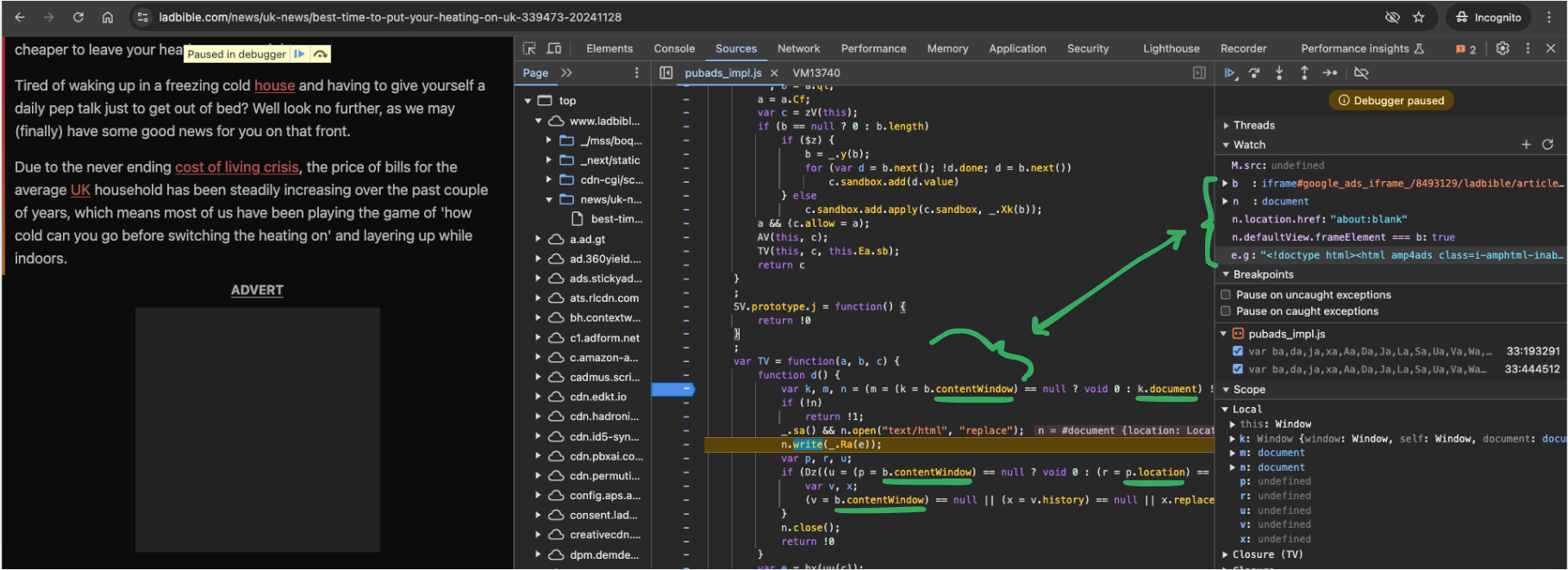

Here’s the part within https://securepubads.g.doubleclick.net/pagead/managed/js/gpt/m202411180101/pubads_impl.js that takes that same-origin about:blank iframe and uses document.write (as well as some other same-origin sync-access APIs) to inject a new ad html into it:

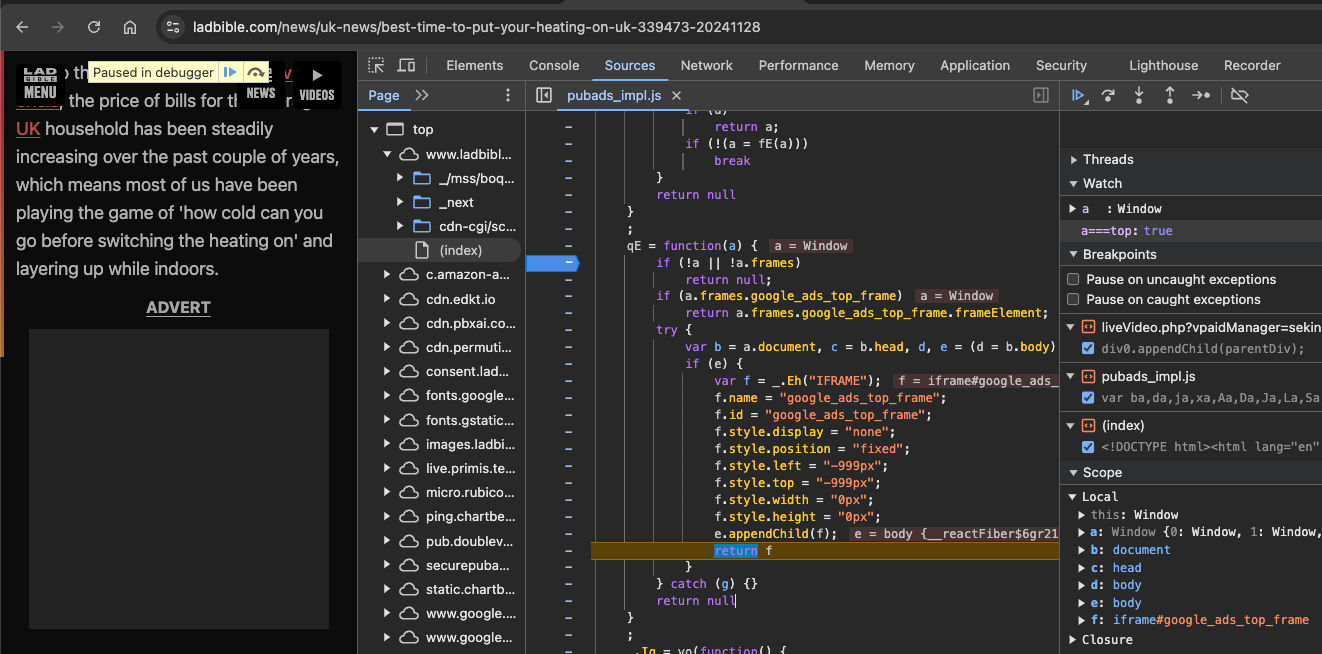

This behaviour was observed on other websites that make use of Google’s ads services, which makes it clear that this well-used script currently depends on the realm-to-realm same-origin sync-access feature. By the way, the same script creates another about:blank iframe and sync-accesses it for other unknown reasons, as can be seen here:

Google (social login)

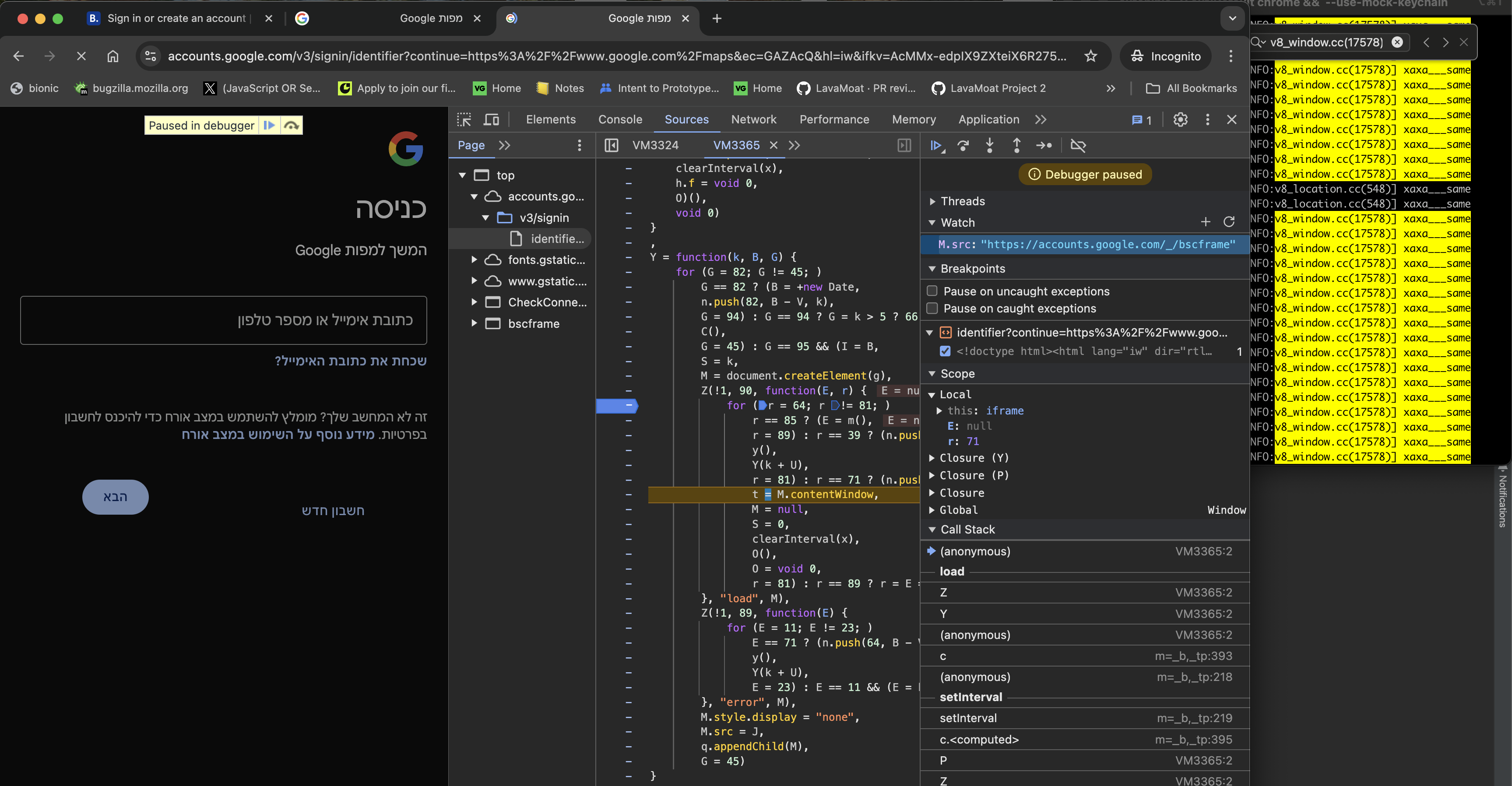

Google’s login page https://accounts.google.com/ServiceLogin?hl=iw&passive=true&continue=https://www.google.com/ also seems to make great use of realm-to-realm same-origin sync-access. Again, it’s hard to tell for what reason, but it does seem consistent. In the image below is where the same-origin iframe they created is being accessed via the contentWindow accessor deterministically:

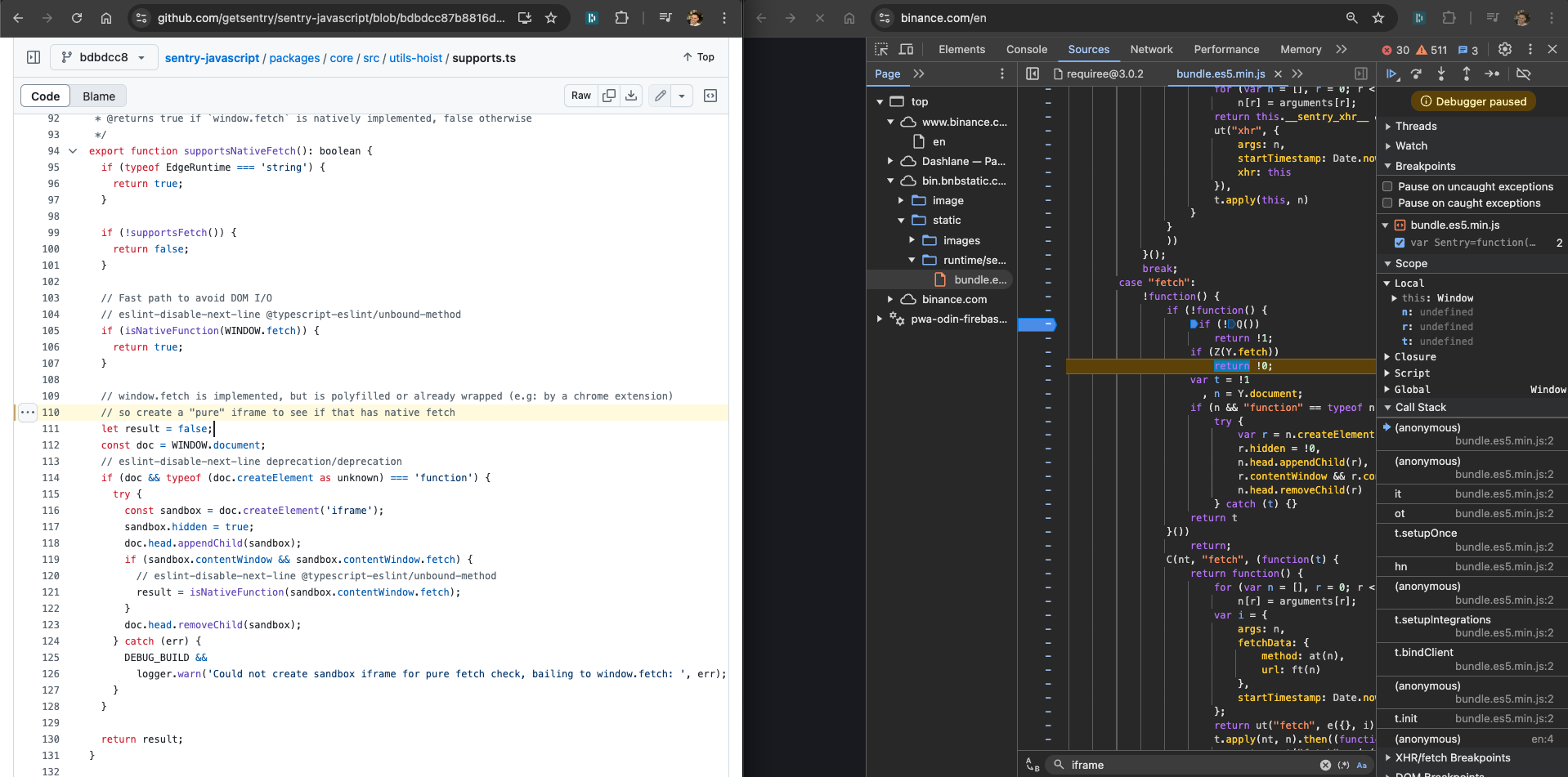

Sentry (metrics)

Sentry also depend on realm-to-realm same-origin sync-access, but conditionally - on init, they create a same-origin iframe and grab a fresh instance of the fetch API only if they conclude that the fetch instance of the top was monkey patched by some other JS code in the page (which is not very rare, depends on what other scripts the website includes).

Facebook (pixel)

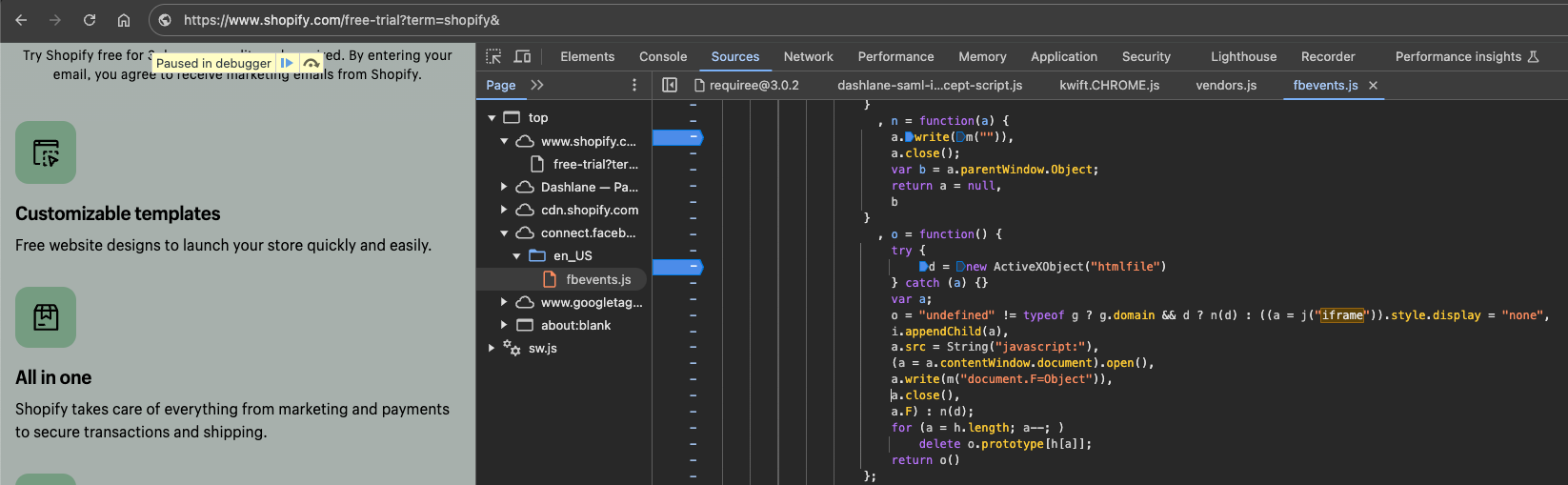

Facebook’s Pixel demonstrates clear indicators for realm-to-realm same-origin sync-access within their super popular third party library https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/fbevents.js which is loaded just about everywhere, but in contrast to the former examples, I was not able to successfully reach the branch in code that actually executes such behaviour:

X (embedded posts)

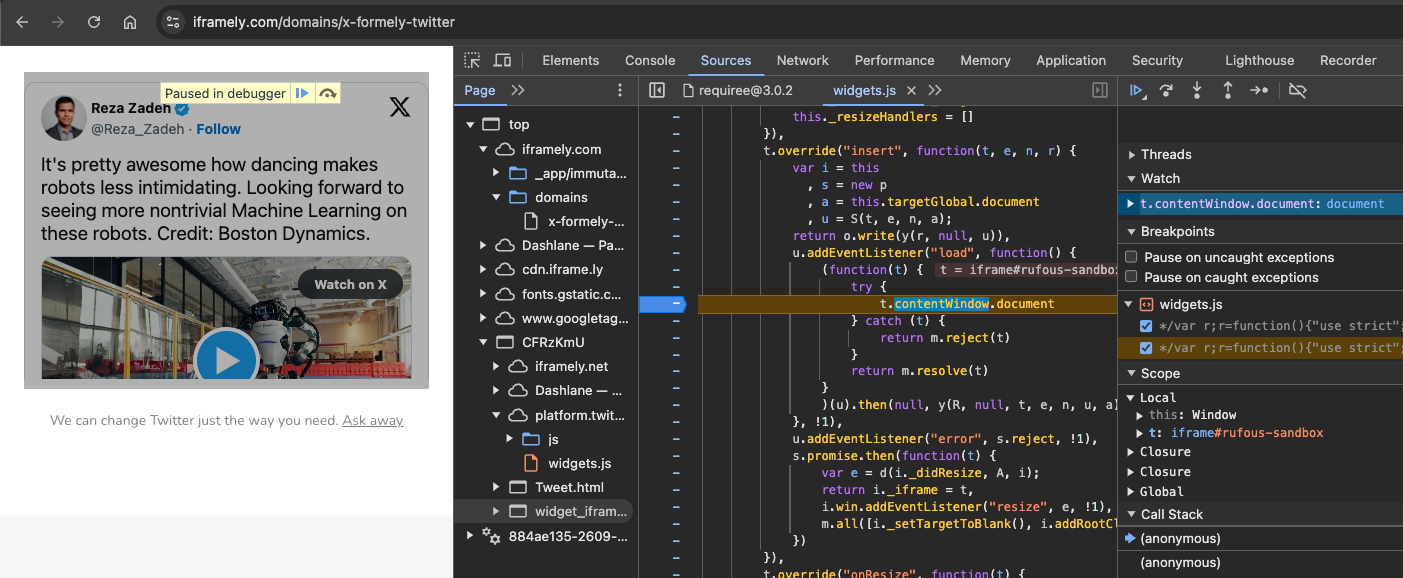

X’s embedded posts via https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js seem to also introduce some same origin iframe IFRAME#rufous-sandbox and to synchronously access its internals for unknown reasons:

Conclusion

Given how the examples above are of sites and scripts that are highly popular and well-used across the web, it seems fair to conclude that without proper adjustments, websites across the web that embed these won’t be able to easily opt into features such as the proposed no-sync one, as it will prevent the scenarios that were displayed above, and thus break them.

I am also positive that by digging deeper, more websites relying on such a feature will be discovered. One ecosystem that strongly relies on this feature is the advertisement industry (Google Ads is just the tip of the iceberg). Therefore, it’s fair to say that a more lax solution such as the proposed RIC one could be opt into without breaking sites nor require them to adjust whatsoever.

That being said, it’s not that the nosync idea is bad. On the contrary - the web could really use something like nosync and I fully endorse it. My point is that it’s not one or the other - there are enough actors in the web ecosystem that deserve proper solutions that will help them sustain. Those who are able to adopt, enjoy superior security by integrating restricitive solutions such as CSP, COOP, nosync and more. While that is the right approach, realistically, it’s clear that a massive chuck of the web isn’t going this way. These websites integrate code flying in from multiple places, all running within a single origin, doing all sorts of things, and getting them to change their ways is a difficult task. Due to that, there are vendors that provide security tools that can integrate with these actors. The RIC proposal allows these vendors to successfully provide this value to these actors, and therefore is important to have, just as much as a nosync-like proposal.

Just as I said earlier - the spectrum is so wide, that both ends of it probably won’t ever meet. It’s our responsability as builders of the web to respect both of those ends and provide them with appropriate solutions for them to thrive.